|

Czech belongs to the western group of Slavic languages. The closest relative of Czech is Slovak. Both languages are easily understandable. Even Polish is quite similar and the understanding is not too complicated. Another relative language is Serbocroatian, but despite many similiraties in vocabulary, the differences in grammar make general understanding harder. Slovenian, although geographically close, represents quite a distant language from Czech. The same is valid for Macedonian and Bulgarian. Bulgarian is the most distant of all Slavic languages. However, the main differences are in grammar (Bulgarian has reduced declination) and reading a Bulgarian text is surprisingly much easier. Russian is situated somewhere in the middle.

Since I am not a linguist and I think that the majority of people need not sophisticated linguistic analyses, I confine myself to a brief overview of the phonological development. I don't recommend to use it as a 100% reliable source, only as an informative overview, because I don't have enough time to watch recent development in Czech linguistics.

The first written records on the territory of Czech lands were in the so-called Old Church Slavic, a dielect of Slavs from the region of Thessaloniki in Greece. Thessaloniki was the birthplace of Konstantinos (+869) and Methodios (+885), two Greek brothers-priests, who came to Moravia in 863, being invited by Rostislav (Rastislav), the duke of the Great Moravia (ruled 846-869/870), to spread christianity among Slavs in Moravia. However, the right aim of this christian mission was not to spread christianity, because Moravia was being christianized since cca 800 by Frankish missionaries; the orientation towards the Byzantine empire was actually to strengthen the position of the Great Moravia against the Franks. For the communication with Moravian Slavs, the brothers used a Slavic language spoken in the area of Thessaloniki that was easily understandable, although it already contained some dialectical differences.

The oldest Old Church Slavic records are written in the so-called glagolica, a script derived from small Greek letters by Konstantinos. This script was gradually substituted by the easier Cyrillic alphabet derived from Greek capitals. Slavic monks were expelled from the Great Moravia after Methodios death (+885) by Rostislav's nephew Svatopluk (ruled 870-894), who again turned to the Frankish empire. The monks then found refuge in various Slavic lands - mainly Russia and Bulgaria. The Cyrillic alphabet then gave birth to the modern azbuka that is today used by Eastern Slavs, Bulgarians, Macedonians and Serbs. Some Slavic priests also fled to Bohemia, where they built a monastery in Sázava. Here the Old Church Slavic survived another 200 years, until the monks were again expelled in 1097. This was the definitive end of the Old Slavic Church in Czech lands. Latin started to be used since the 10th century and after 1097, it was the only official written language in Bohemia.

The first sentence documented in the Czech language comes from the beginning of the 13th century and is contained in the foundantion charter of the canonry of Litoměřice:

"Pauel dal gest plofcouicih zemu Wlah dal geft dolaf zemu bogu i fuiatemu fcepanu fe duema dufnicoma boguceu a sedlatu"

Transcription: "Pavel dal jest Ploskovicích zem'u, Vlach dal jest Dolas zem'u Bogu i svatému Ščepánu se dvema dušnikóma, Bogučejú a Sedlatú." [Pavel gave a land in Ploskovice, Vlach gave a land in Dolany to God and Holy Stephen with two spirits, Bogučej and Sedlata]

Besides, there exist lyrics of songs and prayers like the song of Holy Václav (12th century).

The first continuous written records in Czech language come from the second half of the 13th century (the epos Alexandreis). The sources for the development of Czech language before 13th century are thus only indirect: bohemisms (apparently West Slavic/Czech traits in Old Church Slavic texts), Czech personal or local names, some gloses and short Czech translations of non-Czech words in Latin texts, or short inscriptions.

The historical development of Czech went through several stages: The first stage began in the 9-10 th century, with some important phonetic changes (or preservations) that separated West Slavic languages (then rather dialects) from the rest of the Slavic world. Common West Slavic traits are:

A common Czech/Slovak-South Slavic trait is

Common West Slavic-East Slavic traits are

Changes that differentiated Czech (and Slovak) from Polish (and, partly, from Lusitan Serbian):

After these changes, the Czech phonological system around 1000 had hard labials (p. b, m, v), soft labials (p', b', m', v'), dentals (t, d, n, l, r), palatals (t', d', n'+ň, ľ, ŕ, j), sibilants or half-sibilants (s, z, c, š, ž, č, ś, ć, z/dz'), velars (k, g, ch) and eight vocals (ä, a, e, ẹ=closed e, i, y, o, u). Accent - originally free - was eventually stabilized on the first syllable (around 1100).

The majority of phonetic and morphological changes occured during the 13-14th century. Especially during the 14th century, the development of Czech was very dramatic, so today, reading texts of Jan Hus (+1415) is markedly easier than reading the Dalimil's chronicle, finished around 1314.

The phonological system after these changes was somewhat reduced. The vowel ä disappeared and there were seven vowels (i/y, ẹ/e, a, o, u) that were later even further reduced due to the disappearance of differences between ẹ/e (ẹ > e) and i/y (y > i) (documented by Jan Hus around 1400). The intonation was stabilized on the first syllable, during the 12th century at the latest. Simple past tenses (aorist, imperfectum) were lost during the 14th century. The 15th century gave birth to four diphtongs: ie, uo, ei and ou. Two of them were shortly after monophtongized.

Around 1500, the system of Czech phonology was practically completed: it contained vowels a, e, i (written also as y), o, u, and two diphtongs ou, ei. Long equivalents of short vowels also existed (except ó that disappeared in originally Czech words). The consonants consisted of five labials (b, f, p, v, m), five dentals (d, t, n, l, r), six sibillants (ž, š, č, z, s, c), four palatals (d', t', n', ř) and four velars (k, g, ch, h). Since the 15-16th century, Czech language has changed only little. The development took place mostly in syntax only.

Standard versus Common Czech. The modern Czech language (Standard Czech) is generally based on the medieval literary Czech (approximately its state in the 16th century). It is practically only a formal, bookish language used in media and people don't use it in friendly contacts. The language of normal communication is the so-called Common Czech, which is actually the current form of the dialect of Central Bohemia and especially Prague. This "bilingualism" came into being in the 19th century, during the era of the Czech national revival that led to the renaissance of Czech literature after 200 years of its hard suppression. Since the speech of contemporary ordinary people was uncultivated and expressively poor, the revivalists - among them especially Josef Dobrovský (1753-1829), the author of the Czech grammar - started to use the language of medieval literature. This language norm later became official, yet the speech of ordinary Czechs remained the same and continued in its development. Today some features of Common Czech slowly penetrate into the official language and the differences partly decrease. On the other hand, the bookish language of Standard Czech also influences Common Czech, so one can't say that Common Czech is identical with the central Bohemian dialect. In general, forms of Common Czech are not as advanced as in the central Bohemian language, but their use also depends on the speaker and on the region. Naturally, the more different is the original local dialect, the more local dialectical forms penetrate into Common Czech.

The main features of Common Czech were largely set in as early as during the 15-16th century:

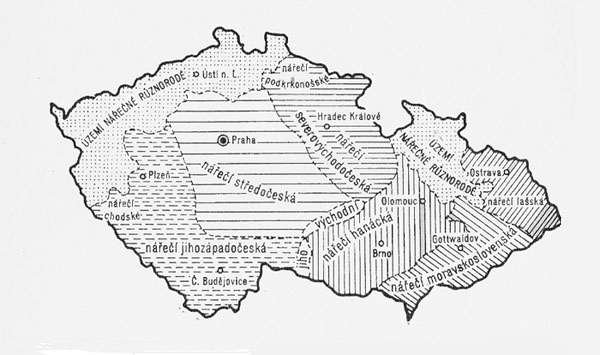

Bohemian dialects. Generally speaking, Bohemian dialects are much more homogenous in comparison with Moravian ones. Since almost every change spreaded from central Bohemia (Prague), bigger differences remain only in remote areas, especially in the Chod region and Podkrkonoší. Borderlines among various dialectical subgroups are thus only very foggy. I can list only some peculiarities:

Moravian dialects. The dialectal division in Czech lands was largely finished in 15-16th century. While dialects in Bohemia were mostly influenced by the central Bohemian dialect and their peculiarities virtually disappeared, Moravian dialects have often preserved archaic features that disappeared in Czech as early as during the 14-15th century. Today, there is much wider dialectical diversity in Moravia than in Bohemia and typical dialectical features are more visible. Although even here Common Czech penetrates into indigenous dialects, the influence is not equally strong in all regions (villages are less influenced than towns and cities) or linguistic cathegories. Some typical Moravian traits have a very tough life. It is also interesting to note that people from Moravia consider Common Czech as very impolite in a formal contact, while in Bohemia Common Czech is not rare even in formal situations (students vs. professors, for example). Moravian dialects differ from Bohemian dialects especially in the lack of umlaut after soft vowels (a > e, u > i). There are also differences in the development of ý+é.

The differences among Bohemian and Moravian dialects can be demonstrated on this sentence:

Standard Czech: Dej mouku ze mlýna na vozík Common Czech: Dej mouku ze mlýna (mlejna) na vozík (vozejk) Central Bohemian: Dej mouku ze mlejna na vozejk Hanakian: Dé móku (móko) ze mléna na vozék Lachian: Daj muku ze młyna na vozik Moravian-Slovakian: Daj múku ze młyna na vozík

Moravian dialects can be divided into three main groups:

1. The dialects of Hana (Hanakian dialects) are situated between the region of Olomouc (Middle Moravia) and the Austrian border. Since I myself come from the South Moravian region, Hanakian (or Horakian, respectively) is my own dialect and I can discuss it in a more detailed way. They can be divided into several groups that differ in the stage of development of some features. In general, Hanakian dialects sound very dully and are a typical "speech of boors". One of the most remarkable features is a narrower pronouncation of i,e that is sometimes caricatured by people from Bohemia. Even a man of Moravian origin speaking perfect bookish Czech can be "betrayed" by his narrow pronouncation. During middle ages Hanakian dialects were influenced by Bohemian dialects and in several aspects, the development of some vowels advanced even further than in Common Czech (probably as early as during the 16th century):

These forms are recently substituted by forms of Common Czech, especially -ej, -ou instead -é, ó, so you will hear children saying rather krásnej mlejn than krásné mlén "a nice mill". The "dull" o, e instead u, y have disappeared almost completely.

On the other hand, Hanakian dialects still preserve typical Moravian archaic features like -a after a soft consonant (práca=Czech práce "work", ruža=růže "a rose" etc.) or -u instead Czech -i in the same cases (hledám prácu=hledám práci "I am looking for a job"). The umlaut actually occured only in the middle of words: Czech cizí x Hanakian cizi x Slovak cudzí "foreign", Czech ležet x Hanakian ležet x Slovak ležať "to lie".

2. The dialects of Moravian Slovaks (or Moravian-Slovakian dialects) can be found in a cca 40-60 km (25-40 miles) wide zone along the Slovak border. They actually represent something like "mixed Czech-Slovak". It is a very beautiful, "limpid" language, richly used in folk songs. In fact, it is the most archaic language in the Czech republic. Similarly like in Hanakian dialects, umlaut ú, u > í, i + a > e exists in the middle of words, not in the end. There is no change é > í, ý > ej. The difference between l'/ł is preserved. Of course, the dialects are not 100% homogenous because of their position between Slovakia and western Moravia that was affected by Bohemian forms, so there exist some peculiar transient regions. For example, dialects near the Slovakian border were influenced by late Slovak colonization and thus they lack ř.

3. The Silesian - or Lechian - dialects are close to Polish and are situated in North Moravia. Their most remarkable feature is the total shortening of all vowels and the accent on the penultimate (the same like in Polish). There are also other features that Silesian dialects share with Polish. Although Silesian dialects still preserve many archaic features better than any other speech in Czech lands, in other aspects they have advanced considerably, so I think that generally speaking, Moravian-Slovakian dialects can be considered more archaic. For example, there exists (almost) no umlaut ú, u > í, i + a > e, no change é > í, the difference between i/y and l'/ł is preserved. Further, there is no syllabic r,l, so these consontants usually go with a vowel y (Czech plný x Lachian pylny "full"). On the other hand, Lachian dialects softened t', d' (t'icho > cicho "silence", d'ed'ina > dzedzina "village") and s, z before i, e (prosit' > prośić "to ask", zima > źima "winter"), which are similar changes like in Polish ("dzekanie"). There are also some vowel changes that differ among various regions of north Moravia.

Silesian dialects are another "speech of boors". When humorists in TV want to caricature a speech of some dull and slow persons, they often immitate the Silesian accent on the penultimate. The dialects in some remote areas in North Moravia contain a big number of German words and can be hardly understandable. For example, once I was in one South Moravian village and I wanted to phone from a phone box in the street, but there was some boy calling his grandmother. When I was waiting in the front of the box, I was attracted by his strange language. At first I thought it had to be something like Lusitan Sorbian or some Polish dialect, but the boy had shocked me, when he had said (in perfect Czech) that he came from one region in North Moravia. I was absolutely stunned, because until that time I have had no idea that people in my country can speak something like this! |